One of my main job functions is to trade electricity. Now, the simple question is… what is that? There’s a lot that goes into that answer, but roughly speaking, electricity trading is the art of guessing supply versus demand. There are many different markets and market types, but I participate in what’s known as the day-ahead market. And that’s what I’ll talk about.

Let’s go back to Economics 101. Something that is inelastic doesn’t respond much to market fundamentals regarding how much people want it. That’s a lead-in to the point that most electricity users have an inelastic demand profile. When you want to turn on the lights, you don’t think about whether the supply is there or what the marginal cost of turning on a light is. You simply flip a switch, expecting the power to be there.

But on the supply side, things are very different. We’ll go into the different types of generation in a moment, but each generation unit type (think wind, solar, nuclear, etc.) has a unique generation and response profile. A coal generation facility can’t simply “turn on the jets” to produce electricity for the two minutes you want a light bulb on.

And finally, as an end-user, you expect to be able to turn on the lights at any time. You want the ability to run the microwave, AC, heaters, computers, and any other electrical devices whenever you need them. Blackouts are simply unacceptable.

There are two solutions to preventing blackouts: perfectly managing supply and demand, or maintaining an excess supply. This leads to the next point: electricity trading is, by design, inefficient. You should always have more generation capacity than demand.

And because there should always be more supply than demand, making money on long-biased trades—where you anticipate electricity prices to be high—should be very challenging. Selling is generally more profitable, but you run the risk of getting blown out.

Timing, like in most markets, is key in electricity trading. Specifically, I trade in what’s known as the day-ahead market, so that’s what my emphasis will be today.

Why does electricity trading exist?

This one is actually an easy answer. We don’t know what demand or supply will be in the future. I have my own estimations, my firm has its estimations, the trader down the street has her estimations, and the trader 500 miles away has his estimations. We all have different views of what the market will do tomorrow. It’s prediction markets at work: taking the consensus of the crowd allows for better accuracy on the expected supply vs. demand curves.

Then what is the day-ahead market

We don’t know what demand or supply will look like tomorrow, but we can make estimations. Traders submit prices into the market at which they are willing to buy or sell electricity. After a complex mechanism run by the ISOs (think of ERCOT, which most people are familiar with), the mechanism calculates what it believes prices will be for each hour tomorrow. These prices help facilitate which generation units need to be started.

We made trades today for tomorrow’s electricity profile. It’s one day-ahead.

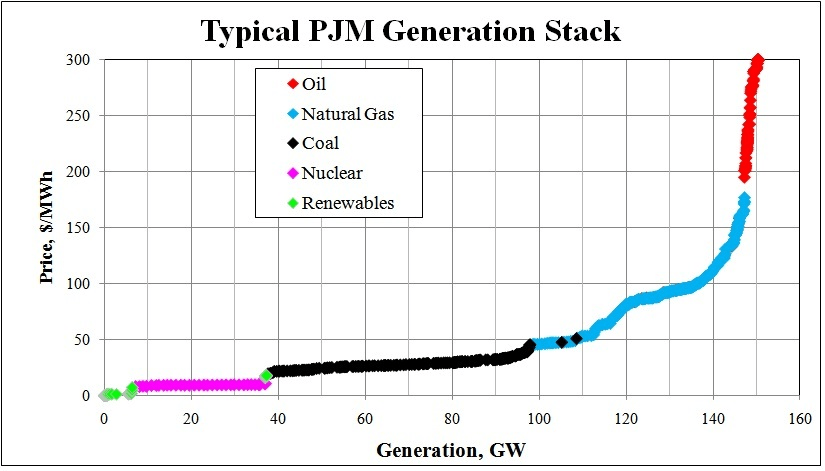

These prices all feed into what’s colloquially known as “The Stack.”

What is the electricity trading stack, and how do generation responses vary

Let’s start with the below image:

If I ask you to think about the different kind of generation units, you may state something like:

- Wind

- Solar

- Hydro

- Coal

- Natural Gas

- Nuclear

- Diesels

Let’s talk briefly about the pros and cons of each one

Wind, hydro, and solar are cheap, but they aren’t reliable. They’re known as intermittent resources: either they are on, or they’re not. Additionally, there may be issues with power transmission due to congestion, but we’re not going to cover that here.

Coal is cheap, though not as cheap, and it takes a long time to turn on and off. Coal plants can take several hours to cycle, so they can’t respond quickly to demand like a lightbulb turning on.

Natural gas is relatively cheap but still requires a few minutes to cycle on and off.

Nuclear is cheap but runs continuously. Shutting down a nuclear plant isn’t easy.

Diesels are very expensive but can be used as resources of last resort.

The key is that each one of these has trade-offs. None of them are perfect. The goal of the day-ahead market is to find the most-efficient allocation of generation resources that still fits the expected demand profile.

How is profitability determined?

DART!

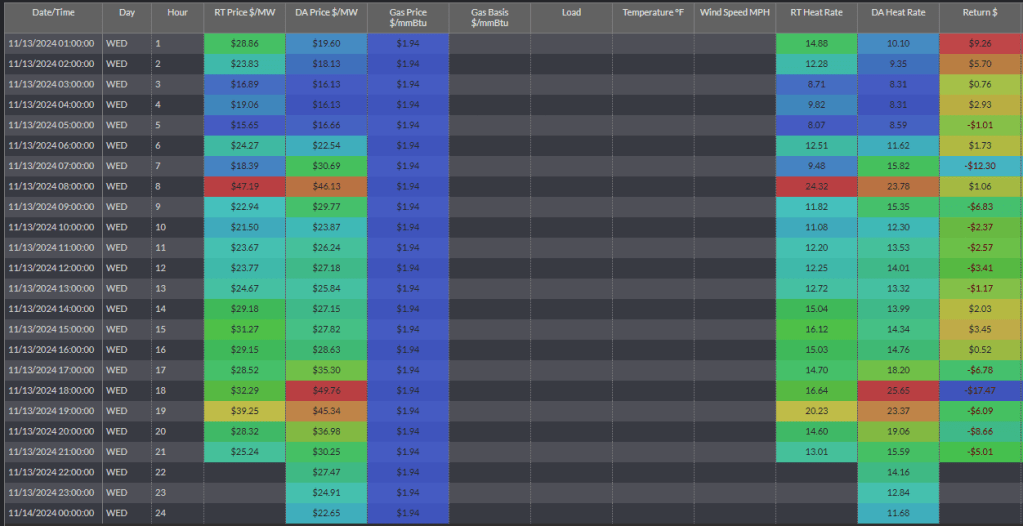

It stands for Day-Ahead Real-Time. That means nothing without context, so what it actually represents is the day-ahead price minus the real-time price. However, most conventions actually review returns as real-time minus day-ahead, so it should technically be RTDA, but that’s hard to pronounce, so we call it DART.

I was just trying to confuse you. You can think of DART as the return you get from bidding on electricity. You submit a price you’re willing to pay for electricity in the markets. If your price clears, then whatever the real-time price is the next day is your return. It’s essentially a CFD, or contract for difference.

So profitability is determined by: the actual price of the next day MINUS the price that you submitted of the previous day.

What’s more profitable, buying or selling?

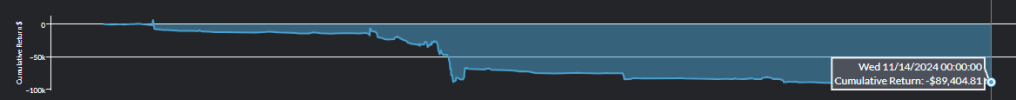

Selling. And it’s not even close. Let’s take the two ISOs I trade in, ERCOT and MISO. Below are the return profiles of some hub-averages over the last two years.

But wait, I thought you just said selling is more profitable, yet the MISO hub has a positive return of $989. And you’re right—until you look at the shape of the curve. There was one large spike day in Christmas 2022, and then it just bled everything off.

Selling is more profitable (in the long run) because you always need more supply than demand, so the real-time price will generally be lower than the day-ahead price. But in the short run, selling may not be profitable and may lead to liquidation. Take MISO’s Indiana.HUB, for example: there was a period with massive returns of almost $20k per megawatt, but then it just bled everything off. If you were long that one day, you’d be feeling great. If you were short that day, you’d be bankrupt, but if you were short every hour after that, you’d be feeling great. Electricity trading is about timing and tail-risk management.

Meanwhile, if you went long ERCOT over the last two years you would have lost $90,000. You make that return if you’re short.

What about congestion and transmission

That’s for electricity trading 102, that’s a whole different animal.

Leave a reply to What did electricity prices do during the winter storm of January 2025? Nothing! – Less Dumb Investing Cancel reply